A life of curiosity: Donoghue on his career in Vermont journalism

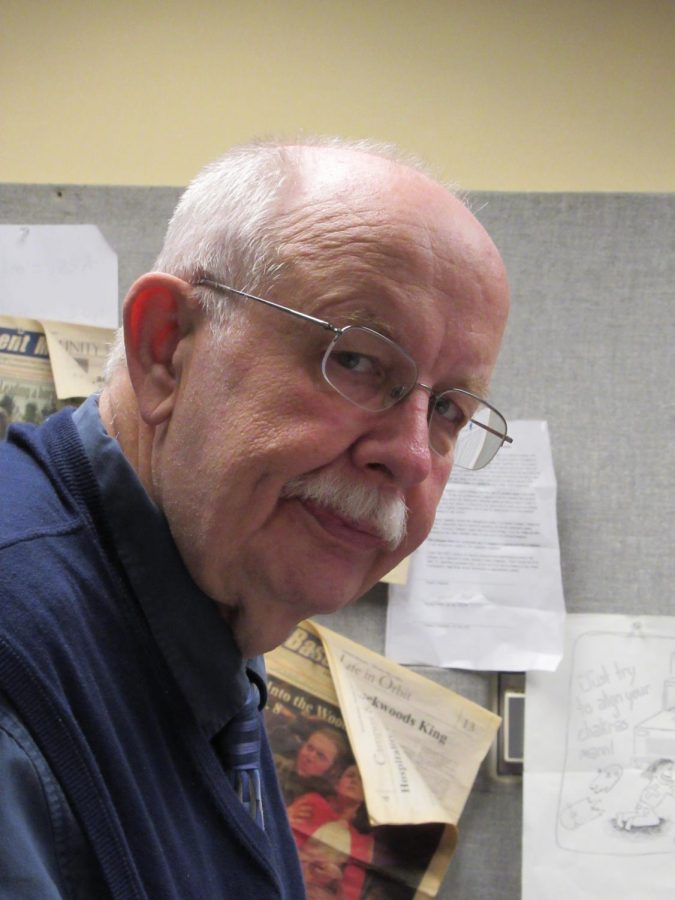

Mike Donoghue

It is a frigid Sunday afternoon and former longtime Burlington Free Press Staff Writer Mike Donoghue is navigating his way back to his native Vermont from Albany, New York, after visiting his in-laws. He is fresh off writing a story for the Brattleboro Reformer about a Winham, Vermont, woman who racked up $1.6 million in fraudulent loans from multiple financial institutions.

Though it has been two years since he retired from the Free Press, Donoghue has continued producing stories for daily and non-daily newspapers around Vermont. For Donoghue, retirement has a different meaning than for other people.

When he was younger, Donoghue and his brother would accompany his late father, John Donoghue, who worked as the internal director of sports information and founded Saint Michael College’s student newspaper, The Defender, to drop off news releases in the newsrooms of Channel 3 and The Free Press.

Donoghue grew curious with the buzzing newsroom, foreshadowing what would later become his workplace.

His first opportunity to write, however, came years later when teacher Rick Marcotte inquired about his life goals one day in the hallway during his sophomore year of high school in the mid-60s.

“I said I didn’t know and he told me, ‘You’re going to start writing for the student newspaper,’” said Donoghue. “We got into a discussion, or a debate if you will; he was quite insistent I was, and I was quite insistent that I wasn’t going to. As always, the teacher wins those, usually.”

He agreed under the stipulation that he would cover sports, though, his interest in sports writing would lead him to the newsroom of the Burlington Free Press.

Donoghue began writing professionally on weekends during his senior year of high school in the late 60s before heading south to attend college at St. Joseph in Bennington, now known as Southern Vermont College. “That was a great job because every weekend was a little different,” said Donoghue. “I would cover things on Saturday and go in on Sunday and typically write up the story that I had covered on Saturday.”

Upon obtaining his associate degree in liberal arts from Saint Joseph College in 1971, Donoghue settled in at the Free Press where he would work for the next 40 years.

Donoghue said he would learn early in his career that not everybody would share his concept of honesty, particularly those in public office.

After receiving a tip in 1974 that former Vermont Gov. Tom Salmon had been pardoning a considerable number of people’s convictions, Donoghue began investigating the peculiarity.

“[The governor’s office] told me that they had given 40 pardons in almost two years,” said Donoghue. “I wanted to see the list and they wouldn’t give it to me, they claimed there was a lot of people who just wanted to go to law school and wanted their record clear. They said they had been arrested for minor crimes like possession of marijuana or minor discretions.”

After arguing that the list of names of pardons be released because it was a public act made by Salmon, the governor relented with instruction from the attorney general. “Just before he was to give it to us, somebody filed a lawsuit to block the governor from releasing it,” Donoghue said.

And after a lengthy series of trials, Donoghue said he “sort of” won his case as he still had to state why he was requesting the list. A Vermont Supreme Court ruling not long after would free the list which Donoghue said featured close to 300 pardons issued by Salmon.

But what Donoghue discovered was another problem. “In fairness to him, there were about 70 pardons that were granted because of a crooked police officer who had framed people in drug cases,” said Donoghue.

“It was sort of an eye-opener for me that cops would lie, because I was brought up to respect police,” he said. “…it was an eye-opener that the governor wasn’t forthcoming with the pardon records when there were a substantial number of pardons that were going on. Those two cases sort of tie in together in the mid-70s, ’74 and ’75.”

Such opportunities to influence change in local government, Donoghue said, became one of his joys of reporting. Donoghue’s acknowledges that his work elucidating injustices in the 1970s, 80s and 90s changed how state government treated several crimes today.

“It is interesting that, as a journalist, you write the first draft of history,” said Donoghue. “Being front and center on both those stories was interesting and being able to have an impact on Vermont. Throughout my career, there have been cases that we reported on that led to substantial changes in Vermont, whether it was on driving while intoxicated cases or how rape victims were treated… it’s interesting to [report] to make things work better.”

One case would lead Donoghue to pursue the story of a female Milton school teacher who went missing in 1980 without immediate investigation. Donoghue promised the missing woman’s family that he would write a story about her every year until she was found.

“We kept doing a story questioning why nobody was doing anything about it and we also did stories saying who the prime suspect was: her former boyfriend who had no alibi for that day,” said Donoghue. “He didn’t go to work and it turned out he ended up shooting her at his house down in Shelburne, [Vermont].

“He took her body and drove it over in her car over in the center of Vermont, dug a grave in the middle of nowhere, buried her and brought the car to a junkyard,” said Donoghue.

According to Donoghue, the murderer fled Washington County by cab and later fled the state. The woman’s body, meanwhile, would remain missing for 10 years before a prosecutor took the case.

The murderer was arrested soon after in California, exchanging the location of the body for a lighter sentence, Donoghue would report. The victim’s family — including her son, who was around two-and-a-half when she was murdered — would have peace of mind. “I was invited to the funeral and the detective who worked on the case for close to the 10 years, but never knew her, did the eulogy at the funeral and talked about [her], even though he never met her.”

The victim’s father initiated a standing ovation for Donoghue and his work at the end of the funeral, which he said was “gratifying.”

“That might be the ultimate,” he said, “to help the parents and her son be able to give her a proper burial instead of being off the side of a road that was almost impassable over in Washington County. Nobody would’ve ever known she was there.”

In 1985, Donoghue was recruited and hired to teach media law at St. Michael’s College as an adjunct professor, teaching alongside his father for a year before his passing. “We were both at Saint Michael’s and probably one of the first or second day of school, I was in the bookstore and I heard somebody say something about Professor Donoghue, and I go, ‘Oh, where’s dad?’” he said jokingly. “‘I wonder where dad is.’ Then I realized they were talking about me.”

Donoghue said his years teaching and advising young journalists in addition to his reporting gave him a sharper eye for his own work.

“Students would come to me and say, ‘What do you mean by this? Or ‘I didn’t quite understand that?’” said Donoghue. “It was good in that sense, that I thought my story might’ve been clear; the editor obviously thought it was clear, but then there are a bunch of readers who don’t know what I’m talking about. Sometimes you write about a story so much that you assume people will know things.”

Donoghue’s work with his journalism students over the next seven years would culminate with Saint Michael’s presenting him with the John D. Donoghue Award in 1992. “I have been fortunate to win nice awards and that’s the one that’s right up towards the top,” he said. “It was an honor to get the John D. Donoghue Award; that does hang in the Vermont Press Association (VPA) office over at St. Michael’s.”

Donoghue credits the awards he has accumulated over the years — including the 2007 Yankee Quill Award and the VPA’s Matthew Lyon Award in 2015 for his commitment to protecting Vermonters’ First Amendment rights — to the teamwork necessary to run a newspaper and to complete any journalistic task.

Donoghue continued fostering the growth of young journalists during the 12 years he directed the Free Press’ newsroom intern program, an opportunity he felt necessary for students to have before graduating.

“What we tried to do with our program was to make sure that they were treated like regular staff members,” said Donoghue. “[We made sure] they were getting bylines that said staff writer and not summer intern or special to the Free Press or anything like that. We wanted them to experience what a real news person would experience.”

One intern, Jeffrey Good, would go on to win a Pulitzer Prize in 1995 for his editorials on the probate court system for the St. Petersburg Times, now called the Tampa Bay Times.

With more than 40 years of work behind him, Donoghue received a buyout in October of 2015 and retired from the Free Press after what he calls a “great run.”

As he travels through the rugged Adirondack mountains with barely a bar of cell phone service, Donoghue ponders the possibility of writing a book, which he says is tempting. But he says it’s likelier that he will continue freelancing for Vermont’s daily and weekly newspapers and go day-to-day for the time being.

When asked what he thinks is necessary for journalists to thrive in 2017, Donoghue revisited what got him interested in his profession all those years ago when he accompanied his father to newsrooms: curiosity.

“I’ve spoken to Southern Vermont College, which is my old alma mater now,” said Donoghue. “I did their graduation speech a year ago and that was one of the things I talked about was curiosity. Be curious. That’s why I say I have one of the greatest jobs ever. I get paid for my curiosity, what a great job . . . When you have curiosity, you’re going to try to find the answers.”