A different way of seeing

Scott Carruthers and the fine art of touch

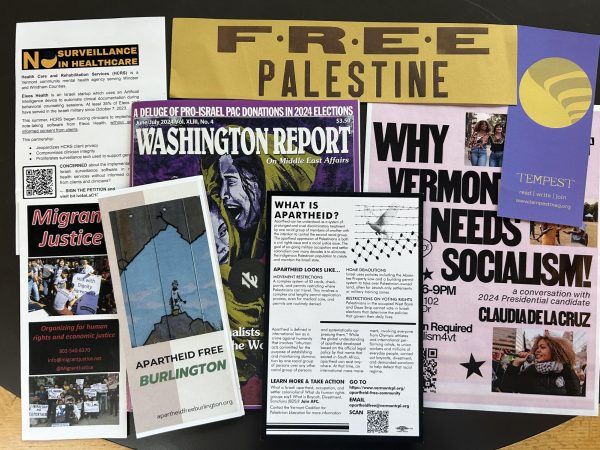

Scott Carruthers feels a classmate’s project.

Scott Carruthers has become a familiar sight, sitting on the cement steps in front of the WLLC with his seeing eye dog, Shannon. A pair of sunglasses rests on his nose and at his side a cane; two things he’s rarely without. It’s clear he has a visual impairment, but what isn’t clear is why a man who can see no more than the point of a pencil in one eye is majoring in the visual arts.

“I’ve always been interested in art, and it just so happens that a lot of art is visual,” Carruthers, a freshman at JSC said. “I see like you; the only difference is I see in a different way.”

A war wound left him legally, though not completely, blind. Serving his country as an army medic in Iraq, Carruthers toiled alongside his men in combing the area for land mines. He said he found most of them; at least one found him.

The bomb took his eyesight and gave him a traumatic brain injury.

“I knew what I was going to be doing with my life,” he explained to his classmates about that time. “Then one day I woke up in another country and everything had changed. I had changed.”

That other country was Germany and he had been in a coma for three days at a military hospital. Now back in his home state of Vermont for more than 6 years, Carruthers, along with his wife Amy, does what every other person does: live from day to day.

“I was frustrated and angry at first,” he said. “But it’s not worth being upset over the past. People need to stop and think about what’s going right more than on what’s going wrong.”

Even before he became a student again after nearly 30 years, he chose an interesting profession for a person with a visual impairment: At his home, he makes custom furniture for clients. Whatever you want made from wood, he said, he can make, although he will refer out if he feels someone else can do better.

Aware of his proficiency with wood carving, however, his sculpture professor Susan Calza plans on pushing him to whet his knife against mediums like ceramics, plaster, steel, and, just last week, marble. With a smile, she reminded him that he came to college to broaden his skills.

As with so many people who lose a sense, his others make up for it, she said. Calza doesn’t think his vision impairment will limit his learning in her class.

“I used to see,” he said, “so I still see things in my head. I walk into the forest and hear the wind rustling in the trees. I feel a leaf and I see the forest around me.”

In the beginning of the semester he illustrated to his teacher what it’s like to be him. Taking a piece of paper, he punched a tiny hole with the tip of a pencil and held it to his face. Through that little dot in one eye, he can discern some colors and indistinct shapes.

There are adjustments to be made, of course. He navigates the campus with his Golden Retriever service-dog. Later in the course while others will use an electric welder for projects, he will need a gas welder so he can see the flame. The safety officer on campus makes sure that Carruthers can safely operate potentially dangerous art tools (he’s already demonstrated expertise with wood equipment).

Other classes are harder for him to compensate for little vision; digital media has a small mouse cursor on the screen for him to keep track of and photography has made him determined to find a system that works so he can take photos without underexposing or overexposing the film.

Even with frustrating aspects of some of the classes, he said he loves this semester. The tactile sculpture class is particularly intriguing, as Calza gave him special permission to touch the art. One of her friends had a showcase at VAC with rock sculptures and gave permission for him to “see” her work with his hands – generally a taboo in the art world.

“I wanted Scott to be able to feel the spirit in the sculpture,” Calza said.

With touch, Carruthers said he can hear rock speak, just as he can hear wood tell him what to do when he’s carving. As his fingers caress the rough edges of unfinished stone or his palms the graceful arch of a marble woman’s throat, he feels the emotions. Anger. Joy. Touching it and being with it is the only way to get to know a piece. Too many people pass by sculptures or paintings without ever meeting them, he said.

“Meeting” art this way actually got him kicked out of the Yale Art Museum, he said with a smirk.

“I can feel the spirit in it,” he said. “When I work with wood or even rock, there’s a texture, a grain, and it already has a plan before I get to it. That’s its voice.”

Calza looks at her students, including Carruthers, the same way she encourages them to look at art. She said she sees in him a person who has been around the world and through immense challenges, an example of a resilient human spirit.

When he learned that, the Purple-Heart recipient’s response was humble: “I don’t know about that. All I know is, like everyone else around campus, I’m just trying to pass my classes.”

Is there a therapeutic value to the visual arts? He laughed and said that if beating on a piece of rock with a chisel and hammer didn’t relieve frustration, he wasn’t sure what would.

Does he ever feel discouraged he can’t see his classmates’ works? Sometimes, but he said before the accident he had been blessed to see some wonderful works of art in his life.

One of Calza’s class projects was for each student to take an old coat and turn it into a work of art. When they were finished, the class gathered in the display room in the front of the VAC to critique one another’s finished products.

Carruthers stood in front of a coat that had been cut up, twisted, and stretched across the wall. He felt it for several minutes, running his hands along the soft contours and over the shredded pieces that dangled.

When it was his turn to offer an interpretation, he said, “Life can become twisted and jagged. You never know where it will take you.”

His project is less surreal and more telling: a homemade soldier-doll with white string for hair and military steel buttons for eyes. Wearing an old battle dress uniform complete with a boonie-style hat, around its neck is a small sign with “PENSILS 5¢” written upon it. The doll stands erect on a small wood plinth. Tied to its waist is an olive drab cord that is attached to another small soldier-doll, lifeless and looking as though it were being dragged behind.

There’s little doubt that this project has a somber story behind it.

No matter how anyone else chooses to view what hardships life has presented to Carruthers, he maintains an attitude that life is precisely what he makes of it. To erase any confusion about how limited he feels by his eyesight, he noted that this winter he will be participating in a biathlon-like sport in which visually impaired people cross-country ski and shoot targets with specialized rifles.

For people who may be wondering what type of rifles, they have an infrared beam and, according to the official Paralympic website, “are assisted by acoustic signals, which, depending on signal intensity, indicate when the athlete is on target.”

True to the original sport, targets missed mean penalty loops around the track.

Many people could take a lesson from his joie de vivre, but the veteran shrugs off anything that suggests he knows a secret that other people don’t.

“You can help people so much,” he said, “but they have to discover inner joy for themselves.”