It was November but I was stuck in September, mostly because I didn’t have anything to be thankful for and I hoped if I gave September another chance something might come up. Monk’s “Misterioso” on vinyl at a garage sale, fifty bucks in a birthday card, a glance I hadn’t met in a coffee shop, something. Still an empty slot among the records, still fifty bucks short, still two seconds slow looking up from my cup of coffee. Time’s punching bag, just like anyone else.

I was thinking about all those women who used to see past the bruises, thinking about all the proposals that would’ve led me down all the paths to all different worlds of happiness, when the phone gave me its own little ring. I said my name to make sure it knew what it was getting into.

A female voice responded. She clarified, “The private dick.”

I said, “Public dick, too, after a few drinks. Can I help you?”

“Someone’s been sneaking into my house. At night.”

“You’re sure?”

“There are footprints. Things are moved. And I saw him the night before last.”

“Did you get a good look?”

“All I saw were shadows.”

“The first line of my memoir, Miss…”

“Scrue. Anita Scrue. I’m a model.”

“Model what?”

“Beg your pardon?”

“Citizen, Christian, public servant…”

“No,” she said, “I model for a living.”

I left September. I felt like a turkey thinking it, but anyone who made me wonder about her stuffing before we’d even met was a reason to be thankful.

I asked if she’d call the cops. She said they’d dismissed her as paranoid. I told her I’d dismissed them as mistakes. She didn’t laugh. I told her I’d be over in an hour. She thanked me.

An hour later I made good on my promise. It was the warmest November evening I’d ever felt outside of a fuzzy blanket and with my clothes on. But it got a hell of a lot hotter when she opened the door.

She had the kind of look that gasped, “Paris!” – I could see unshaven, over-excited Parisian papparrazzi worshipping on the pavement as her walk parted doves. She was lean, thin, even, slender-boned, with whispy hair put up and the raccoon shadows around the eyes that seemed to signify beauty worthy of Parisian import. If I didn’t catch the person sneaking into her house fast I was going to catch myself doing it.

“Miss Scrue, I hope.”

She said, “Come in,” not impolitely, and held open the door. It was a lovely little house. Just a couple small windows in the living room. Plenty of shadow around the corners. The dim lighting arrived courtesy of a small stone fireplace, in which a fire was burning that made all Prometheus’s struggle worth it.

I sat in a comfy armchair without being invited to do so. Everything in this house sang like sirens. My blood was screaming. The chaos I could cause given a night in this place with two bottles of wine, a maid’s duster and an Ian Fleming paperback.

She re-entered with a cup of coffee in a short, round porcelain tea cup, of course. She bent over to hand it to me. I noticed the gentle curve of a smooth, supple white breast, imagined the perky, tight secret at its end.

I thought, “Reel it in, Dick, or this turkey’s going to be coated in its own gravy.”

I said, “When did this begin?”

“A few weeks ago. Two weeks ago.” She was sipping her own coffee. Mine was damn good, a European brew. No surprise. I wondered how she liked hers, and what she put in it. After another sip, she said, “I heard a noise. But that’s all it was, a noise. Until the next night. Then I heard the footsteps.”

“Did you investigate?”

She nodded. I liked that she was verbally conservative. She looked at the oakwood floor while she remembered, and I liked that, too.

“I tripped. I fell down the stairs.”

“What did you trip over?”

“A foot,” she said, as she met my eyes.

My bladder went and her eyes went with it, down to the hot liquid leaking out of my pant legs. She cried, “Oh!” and leapt up, pulling out the cloth napkin from under her coffee cup, which she used to wipe down my legs.

I apologized. “It’s been a while,” I said. “I’m a little rusty.” She took the napkin into her kitchen, then came back.

“Miss Scrue… who do you think is sneaking into your house?”

She thought in silence. I liked that she didn’t have an answer prepared. I liked the picture of her as a child with her grandmother on the foyer, I liked the copy of Shakira’s album “Oral Fixation: Vol. 2” on the mantle, open, CD gone, as though she’d shut it off just as I arrived. I liked her silence and the noise I heard beyond its glass. Hell, I’d have liked her copy of “Mein Kampf” – if Raymond Chandler’s “Pickup on Noon Street” wasn’t IN ITS PLACE OH MY GOD –

“I don’t know,” she said. “I can’t think of anyone.”

“An ex-boyfriend?” I suggested.

“I haven’t had a boyfriend in over a year,” she told me. “We split amicably.”

I wondered if she was the type who had never struck a match under sex or if she was just too busy stoking other fires. I realized “stoke” needs very little to become “stroke” –

“Tell you what,” I said, redirecting my blood flow. “I think the best thing would be for me to stake out your house. If that’s alright with you.”

“Of course.” She rose with me. “Whatever you think is best.”

We stood at the edge of darkness in the living room, half draped in shadow, half blazing with the fire’s light, facing each other, looking into each other’s eyes. My heart rose, stretching upward, pulling on its strings.

In the next second, she could move toward me, and I’d fall against her, the wind carrying her hair’s scent, so clean and alive and weightless, and my thick lips would lose themselves between her slim lips and we’d get lost: descending into each other we’d grow angel wings and float upwards, getting the hell out of this shithole life and into that elusive plane of existence – living.

The next second was the same as the one before it. We were looking into each other’s eyes, but only one of us was looking into the other.

As she let me out, I said, “Miss Scrue – how did you hear about me?”

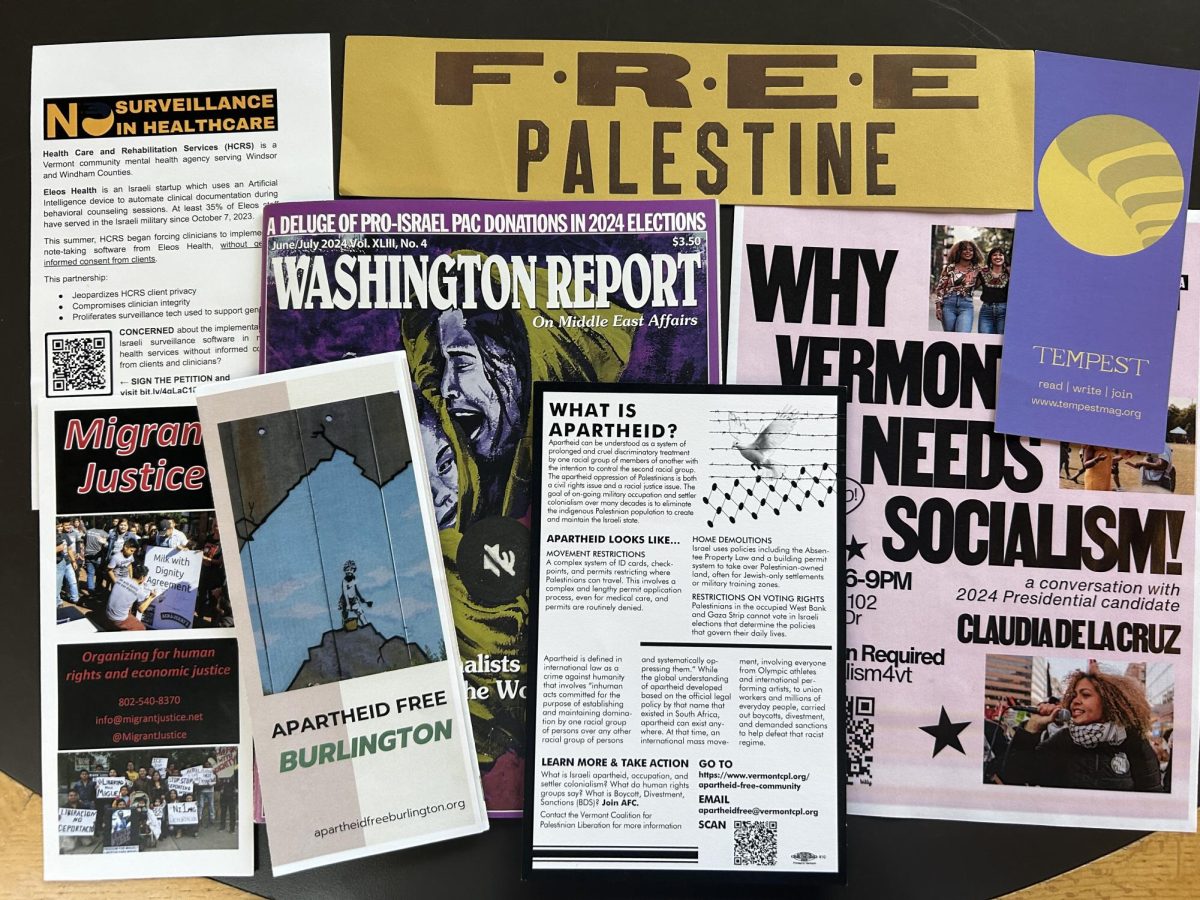

“The Basement Medicine. I found one on the pavement.”

“I didn’t think anyone read it, not my stuff, anyway.”

“I did.” She paused. She held my eyes. “But it wasn’t credited to ‘Richard’…”

“It’s a long story no one cared to read.” Then I said, “You might hear it before we’re through.”

She smiled. “Goodnight, Mr. Schlong,” she said. I told her I’d be right outside, and she closed the door.

SHE SMILED AT ME OH MY GOODNESS A PRETTY LADY SMILED AT ME OH GOD I WONDER IF SHE – I was so rusty if you put me through a wood chipper sundials’d come out. I had to get it together. A sudden smile is just an ambiguity, and that’s that.

Then again, ambiguities are mysteries, and mysteries are coal for the furnace. I let my heart shovel it in, then I got in my car and started to wait, feeling thankful.