Editor’s Note: This piece has been reprinted from ‘Castleton Spartan.’

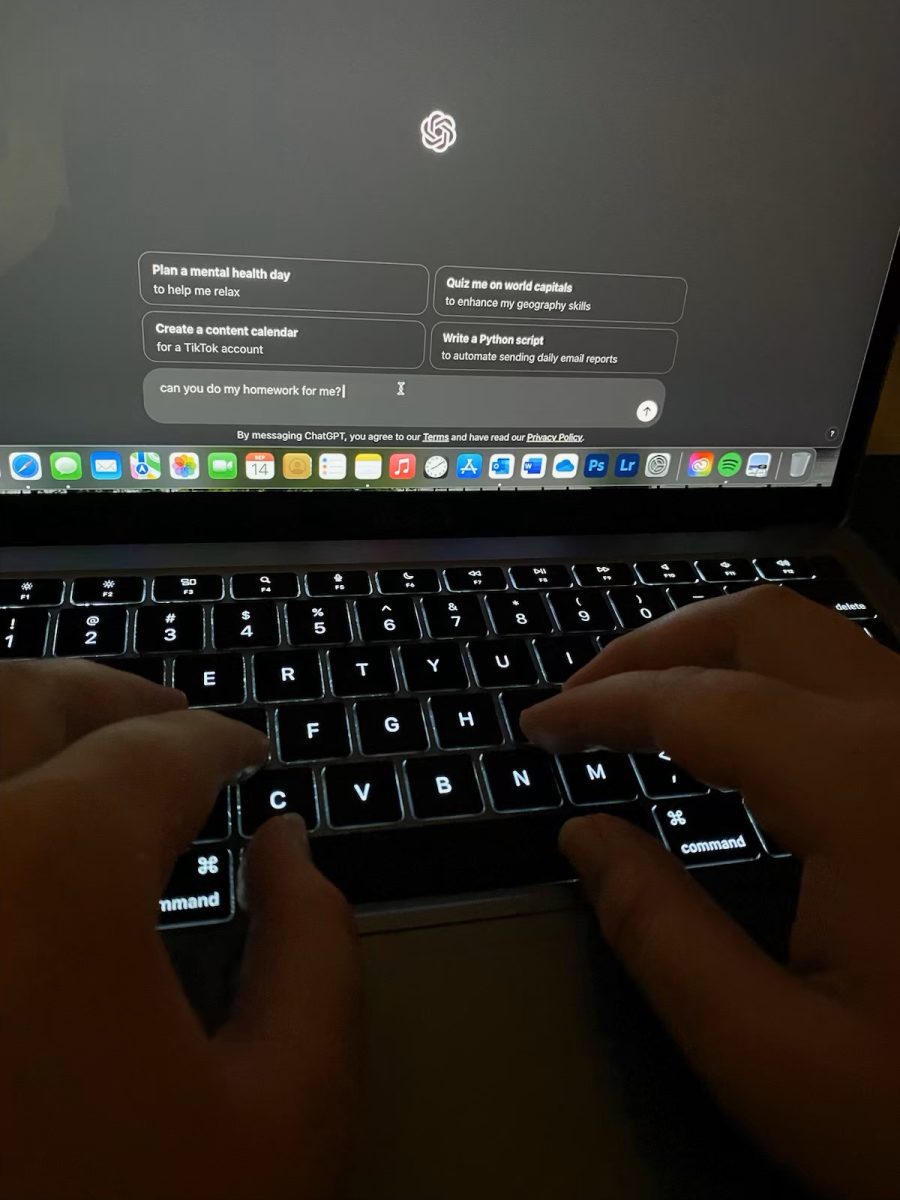

In a world where AI can write your essay and answer all your quiz questions, students are left wondering: Where’s the line between using AI as a tool and letting it do the thinking for us?

That line sounded good, right? Well, it should! It’s hot and fresh from the Chat GPT press. With one simple prompt, a list of 10 foolproof, human-like sentences perfectly curated for this article were created.

Now, more than ever, AI (artificial intelligence) is becoming more accessible and widespread, especially in the classroom. But as the use of AI becomes more normalized, the question is, when does it go too far?

“Obviously, there is a line to AI. Do I know what that line is? I don’t,” said VTSU Castleton communications professor Sam David-Boyd.

In Davis-Boyd’s classes, she discusses and acknowledges her thoughts on AI, but her advice to students is simple: “I’m not saying don’t use AI. I am saying don’t cheat.”

This statement remains almost the same among educators and students alike.

Professor Michael Talbott, chair of VTSU’s Arts and Communications Department, compares AI to tools used in construction.

“A tool can’t build a house for you, but you can use it to build a house,” he said.

Talbott sees AI as a valuable resource, especially for students who struggle to get started on assignments.

“AI can help you turn corners when you get stuck,” he says. “It can help you figure out where you might go next when you run out of ideas.”

Yet, for VTSU-Castleton students like Tim Keeler, the use of AI feels like a shortcut.

“I just think it’s really lame, honestly,” Keeler says. “I think you should be able to come up with your own ideas rather than having a tool give you ideas. I’m smart, and I can come up with my own ideas. I don’t need a tool to do it for me.”

There’s also the risk of students relying too heavily on AI, which has backfired. Keeler recalls a story about one of his friends at West Point, a military school in New York. This student got into serious trouble for using AI-generated suggestions from Grammarly Premium on one of his assignments. After submission, his paper was flagged for excessive AI use, and the student nearly faced expulsion, and ultimately had to redo an entire year of college as a result.

Castleton students like Daniel Lee Wright III and Zoe Ukasik have echoed their concerns on the reliability of AI and how much it actually knows. Lee Wright says he “asked Chat GPT how many ‘R’s’ there are in ‘strawberry,’ and it said two.”

Ukasik has a similar story.

She asked ChatGPT to create a list of five-letter words ending in eo. Upon this request, ChatGPT responded with “ideo” and “video” saying these were the only five-letter words ending in eo.

“What about rodeo?” Ukasik pointed out.

Though these errors seem small, and could be harmless in casual settings, they show the true unreliability of AI.

Some students advocate for explicit policies. Keeler says that he believes “teachers should definitely acknowledge AI, especially in the syllabus.” Though he has never used any sort of AI, he acknowledges many people have and will.

“People are going to use it. So, teachers should at least come up with some sort of policy on AI, whether they allow it in some regards or don’t allow it at all.”

Three other students interviewed agree with Keeler’s statement and that the key to AI is how it’s used.

For some students, AI provides a much-needed boost of inspiration or clarity.

“I’ll ask it (Chat GPT) for examples or help with formatting,” Lee Wright said. “Outside of school, I use it for things like finding good song prompts or chord progressions.”

He sees it as an escape from writer’s block, offering a gentle push to keep his creativity flowing.

Even though AI can help students get started or assist with brainstorming, educators stress that it must be used thoughtfully. Talbott points out that AI is not a replacement for critical thinking.

“AI can be a great point of entry,” he said. “But students who ask AI to do their assignments for them are going to get caught. It’s plagiarism, and it’s not a good use of the technology.”

As AI continues to evolve, the conversation about its role in academia will only grow more complex. Heather Wood, a Castleton student, believes that AI could lead to a decline in intellectual rigor.

“I think AI is going to create less intelligent people,” she said. “Because people are going to rely on the internet, and when the internet is gone, what will we do then?”

As students and educators grapple with the overall ethics of AI, one thing is clear: the line between AI being a helpful tool or an intellectual crutch is still being drawn. Navigating this gray space responsibly may become one of the defining challenges for both students and educational institutions in the future, but let’s heed on the side of caution.

Wood put it simply.

“It’s a gift, but it’s horrifying. People start relying on it to get things done, which can correlate to a less intellectual nation,” she said.