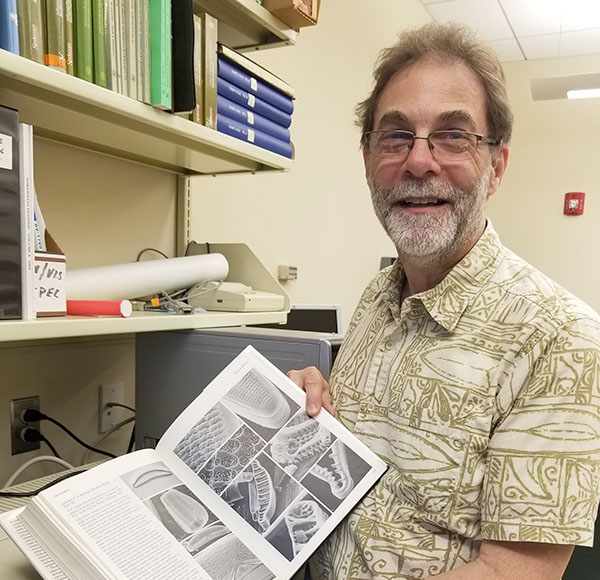

Delightfully devoted to Diatoms: Genter to retire from teaching after fall 2018 semester

A diatom is a microorganism that lives within water, from oceans to rivers to lakes and canals. Scientists can measure water quality based on how diverse in diatoms a stream or river is and if the ecosystem is healthy or not.

If Johnson State’s Environmental and Health Sciences department were a river and the professors were its diatoms, Dr. Robert Genter would be an indicator of its health. Since 1986, Genter has been teaching ecology and biology courses for the science department while simultaneously helping to further research in his field.

“I’ve been able to teach field courses,” says Genter. “I’ve taken students to Maine to look at the intertidal life there many times. I’ve taken students to Idaho, to Yellow Stone National Park, five times.” Genter has taken students on a number of exhibitions in the name of science, usually with the goal to collect information on microorganisms to understand what a healthy body of water looks like.

After 32 years at the college, however, Genter will retire from teaching at the close of the fall 2018 semester.

While he will be leaving the classroom, he has no intention of leaving research. “I’m getting older,” says Genter, “and as you get older you realize how little time there is left. While I’m able, I want to focus on the reason I got a PhD, which was to do research. And so, I want to work with the diatoms.”

Genter’s love of diatoms is well known and has even become a part of his identity in a way. “He finds his happy spot by himself, staring down the microscope, giggling,” says Environmental Science Professor Leslie Kanat. “His specialty provides students with an understanding and guidance that no one else can do.”

Among his many ongoing projects is the artificial stream he has been working on, located on Bentley’s third floor green house. Additionally, one can find more of his fieldwork in the research lab on the second floor, where a large poster he created hangs,depicting the evolution of diatoms with pictures he had taken himself with the high-quality camera attached to a microscope, and another classroom/field lab on the ground level, where field equipment is stored, from homemade sampling vacuums to highwater gear.

He has published several essays on his research, much of it done with an old model of the artificial stream.

He hopes that for the next five years, he can recruit some students to help with his endeavors. While Genter’s teaching style is very field-work heavy, it still pulls him from his research.

Of course, teaching is one of the reasons he’s been in Johnson for over 30 years. “I love learning with the students, so I’ll miss that social part,” says Genter. “Teaching is the biggest social part of my life right now.”

Genter’s love of water can be traced back to when he was a child. He recollects that a friend’s family would go camping in a cabin they owned in northern Michigan. When they had bait minnows left over after fishing, they would give the surplus to the then-8-year-old Genter. “So I would keep these little minnows alive in a little fish bowl,” says Genter, “which evolved into an aquarium. Eventually I had nine aquariums.”

In his early teen years, he subscribed to tropical fish hobby magazines, which he would read cover-to-cover every month. “Now I look back at that and I realize that as a kid, I was living as a scientist,” he says.

Currently, Genter has narrowed his collection to two tropical fish aquariums, one around 95 gallons and another 30 gallons.

Another aspect of his career that Genter loves and will miss dearly is his aid in helping students see the beauty in biology and helping them get jobs after they graduate. “We have a bunch of students working for private firms or teaching or working for the state government, even federal government, who got their start with field work here at Johnson,” says Genter.

This love of research and teaching is evident in how his students view him. “Bob’s clear enthusiasm for his research and interests are infectious,” says senior biology major, Shavonna Bent, who has worked with Genter closely for the past four years. “I never imagined caring so much about diatoms, but it’s hard not to when you have a professor that makes the subject so interesting and engaging.”

Bent even says that Genter has influenced her future career. “Bob has shared a deep passion for water quality and aquatic life that has shaped what I want to do in the future,” she says.

When Genter is not impacting students’ lives or giggling down the lense of a microscope, one can find him making beer in his home brewery, occasionally picking up the acoustic guitar, and raising his son with his wife, Leila Bandar, who works in Academic Support Services.

When asked if he could see any interest in the sciences in his son, Genter says, “He loves spiders. He meets a lot of kids who were raised to be afraid of spiders, but we haven’t raised him that way. We’ve raised him to have a more open mind toward living things, and whether he realizes that or not, I think he does have that perspective.”

Genter’s ability to help change people’s perspective is one quality that will leave an impression on his students and his colleagues alike. “I believe that the students he has taught and inspired will continue to make a difference, and that is a truly great legacy for an educator,” says Bent.

Kanat believes Genter’s hands-on teaching style is what makes him truly standout from others. “He has the ability to take students from an intro class and engage them in some aspect of his [own] research,” he says.

Whether it’s leading an expedition to the beaches of Maine, collecting data from the artificial stream, studying diatoms or brewing beer, Genter will be missed by many who have worked with him in the 30 plus years he has worked in Johnson.

“I look at myself as being a part of a system,” says Genter. “And for my colleagues, we’ve all been working together. We have different points of view, and that’s okay. Being able to be honest about our differences and discuss them is something we need to keep doing . . . The purpose of a democracy is that we all get to speak our mind, we vote, and then we move on. We’re still a team. So that is, I hope, what we all continue to do. And whether I have anything to do with that legacy or not, I don’t know.”