Youth exposure a main concern following cannabis legalization

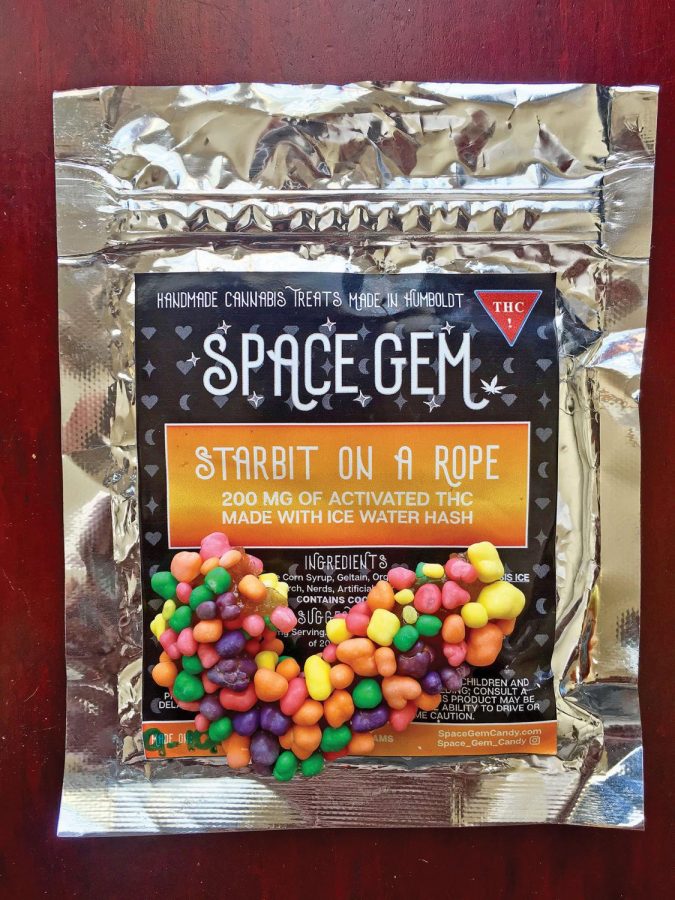

THC-infused candy

For VSC students, the start of the spring semester was accompanied by a letter from chancellor Jeb Spaulding. In that letter, Spaulding explained that, despite Vermont’s landmark legislation legalizing recreational possession and use of up to one ounce of marijuana, the VSCS would not be changing its policy regarding marijuana on campus.

While the policy remaining the same didn’t come as a surprise to many, the necessity of Spaulding’s letter is representative of a larger issue that lies at the heart of marijuana reform: youth access and the plant’s pervasiveness in schools.

Each state that has legalized recreational marijuana has taken a slightly different approach to education and youth prevention including community education grants, online resource centers and public health hotlines. Perhaps the most widespread is the Drug Impairment Training for Educational Professionals program (DITEP).

The program first came about in the 90s as an offshoot of the Drug Recognition Expert program and was brought to Vermont in 2006 by police sergeants James Roy and Todd Ambroz.

“The overall objective of the program is to provide skills in an effort to make the academic environment the most conducive to good learning and functioning for all students,” Roy said. “We’ve kind of reinvigorated our emphasis on getting it out there.”

The program takes place over the course of two days and is done for free anywhere a location is provided.

Day one focuses on policy and procedures, drugs in society, documentation, drug classifications and symptomology. The second day is built around polydrug use and teaches educators how to perform eye examinations, test vital signs and complete the impairment assessment process in order to better diagnose an appropriate course of action in dealing with impaired students.

Six months ago, Governor Phil Scott established the Marijuana Advisory Commission to address issues surrounding legalization. The commission was split into three subcommittees, each tasked with its own subject to research and report on: roadway safety, taxation and regulation, and education and prevention.

The education and prevention subcommittee’s main focus was to examine the best way to measure and reduce impacts on public health, mainly the regulation of THC concentrations in edibles and the “practical implications of the risk of harm to Vermont’s youth.”

In the past, law enforcement has been called in to deal with impaired students in the classroom, even though they’re more of a distraction than a safety risk in some situations.

According to Roy, another hope of the DITEP program is to get educators, school nurses and administrators comfortable enough in dealing with these cases to minimize law enforcement’s involvement.

Ultimately, the goal of DITEP is to reduce drug use and disruption in schools, and any accidents that would come as a result of students driving to or from school while impaired.

While a Youth Risk Behavior Survey showed that marijuana use in Vermont high schools decreased by 10 to 13 percent from 1995 to 2005, a National Survey on Drug Use and Health stated that monthly use in the middle and high school age range still outpaced those aged 26 or higher.

An immediate effect of marijuana use is a decline in grades. In 2015, of the Vermont high school students who reported regularly using marijuana, 48.3 percent got mostly Ds and Fs, with only 14.4 percent getting As.

Multiple studies cited by the education and prevention committee illustrate lifelong adverse effects caused by frequent marijuana use as an adolescent. These include increased risk of anxiety disorders and schizophrenia, even if the individuals had stopped using marijuana.

The subcommittee’s report also noted several studies that linked early and continuous marijuana use to increased risk of not completing high school, not enrolling in or completing college, low educational achievement levels, lower income, unemployment and welfare dependence as an adult, premature work force retirement due to disability and reduction in IQ in middle adulthood.

These reports emboldened Scott’s concerns, which he expressed to the Senate last May in his S.22 veto message.

“This bill appears to weaken penalties for the dispensing and sale of marijuana to minors,” Scott said in the address. “. . . We must acknowledge that marijuana is not alcohol and it is not tobacco. How we protect children from the new classification of this substance is incredibly important.”

As a result of Scott’s message and the commission’s subsequent findings, H.511 imposed much stronger penalties for use around children and dispensing to children.

Firstly, the bill as enacted states that any cultivation must be done at a private residence screened from public view and in a secure location inaccessible to anyone under 21. Any violation will result in fines upwards of $500.

Dispensing or enabling the consumption of marijuana by a minor carries a penalty of up to two years in jail or up to a $2,000 fine or both. If said minor kills or injures him or herself, or anyone else, as a result, the jail time increases to potentially five years and the fine increases to potentially $10,000 or both. This is only if the enabler is over 21.

Depending on the age of the enabler or dispenser, the penalty could be Court Diversion or smaller fines if the victim is younger.

Anyone under 21 who violates the new law will be subject to Court Diversion and will have to enroll in the Youth Substance Abuse Safety Program (YSASP).

YSASP is a program designed to hold youths accountable for breaking the law. Beyond marijuana use and possession, it is also for minors who possess alcohol or are intoxicated in any way. Minors with potential substance abuse problems are identified and educated about the potential harm of using drugs or alcohol so that they can receive treatment.

According to statistics from the Court Diversion program, about 2,800 people a year are referred to YSASP through law enforcement, 81 percent of whom complete the program successfully.

In addition to counseling, participants are required to complete community service hours, which results in about 7,500 volunteered hours each year.

In certain cases impaired students are referred to the YSASP program, which is another reason Roy says the DITEP program is so important.

“One is identification. Two is proper counseling and treatment, or whatever the school system feels is needed for that student,” Roy said. He estimates that well over 2,000 educators have gone through the DITEP program and have been trained to aggressively identify signs of impairment in the classroom.

While the program has been popular for years, Roy said there have been requests more recently for shorter, marijuana-specific programs designed for parents and community members.

The shorter sessions would focus more on what marijuana is, how it works and specific identifiers.

The trend of parents and community members seeking information about marijuana has been on the rise in Vermont.

At a panel discussion in Stowe earlier this year, about 40 people gathered to express their concerns about legalization and hear from marijuana advocates Joe Veldon and Laura Subin, as well as from Lt. Gov. David Zuckerman and Stowe Police Chief Don Hull.

The majority of those in attendance were parents with children either currently in schools or who had already been through the schools. Beyond the main concern of public safety, there was substantial discussion about the issue of marijuana candies and the concentrations of THC in them.

The issue of marijuana-laced candy has been at the forefront of discussion in other states that have legalized recreational marijuana because of the danger it poses to children.

“Certainly, one of the issues in Colorado was the issue around edibles that were in the form of children’s candies,” Zuckerman said. “We certainly don’t want edibles to look like children’s candies and all of a sudden you’re at the house saying, ‘Well, five of these have cannabis and five don’t and I can’t tell which.’”

The panel went on to discuss a 2014 article in the New York Times by Maureen Dowd. Dowd described an incident in Colorado where she decided to try a THC-infused chocolate bar. When she didn’t immediately feel anything, she decided to eat the entire bar, about 16 doses in all. She then spiraled into an existential crisis, during which she thought she had died and no one told her.

Vermont has dodged this metaphorical bullet for now, since the Legislature shied away from a full-blown tax and regulate system with profit-based marketing, but another prevailing issue regarding youth safety and marijuana is its use by pregnant women.

The education and prevention subcommittee reported that there was a 62 percent increase from 2002 to 2014 in pregnant women who had reported using marijuana in the last 30 days. The report also noted a trend of “internet posts promoting marijuana to treat pregnancy-related nausea.”

A 2016 study, “Long-Term Offspring Outcomes,” found substantial evidence that pre-natal exposure to marijuana “adversely perturbs fetal neurodevelopment” and “predisposes the offspring to abnormalities in cognition and altered emotionality.”

While H.511 establishes harsh penalties for the dispensing to and enabling use of marijuana around minors, it stops short of spelling out any penalties for its use while pregnant. This is despite the commission’s strong recommendation to encourage pregnant women not to use marijuana.