Self-stigma: adding insult to injury

She stands motionless at the kitchen sink. Her head is down, freckled cheeks tear-stained. One hand holds up a small orange bottle and she studies the label mutely. Every drooping line of her body signifies her defeat. Behind her, babbling a steady stream of delighted incoherence, a baby plays happily on the floor.

Angry voices from her past fill the woman’s head: her parents mocking the mentally ill; her mother railing against the pharmaceutical system as “nothing more than a money making machine set up to lure you in and get you hooked”; an entire church body preaching that good ol’ American “pull yourself up by the boot straps” cure for depression.

The woman at the sink is me, almost five years ago. I had just been diagnosed with bipolar II disorder and filled a prescription for a mood stabilizer. I stood there scared and ashamed, worried about what people would say if they found out and blaming myself for lacking the strength of will to fight the symptoms of a disease bigger than I was.

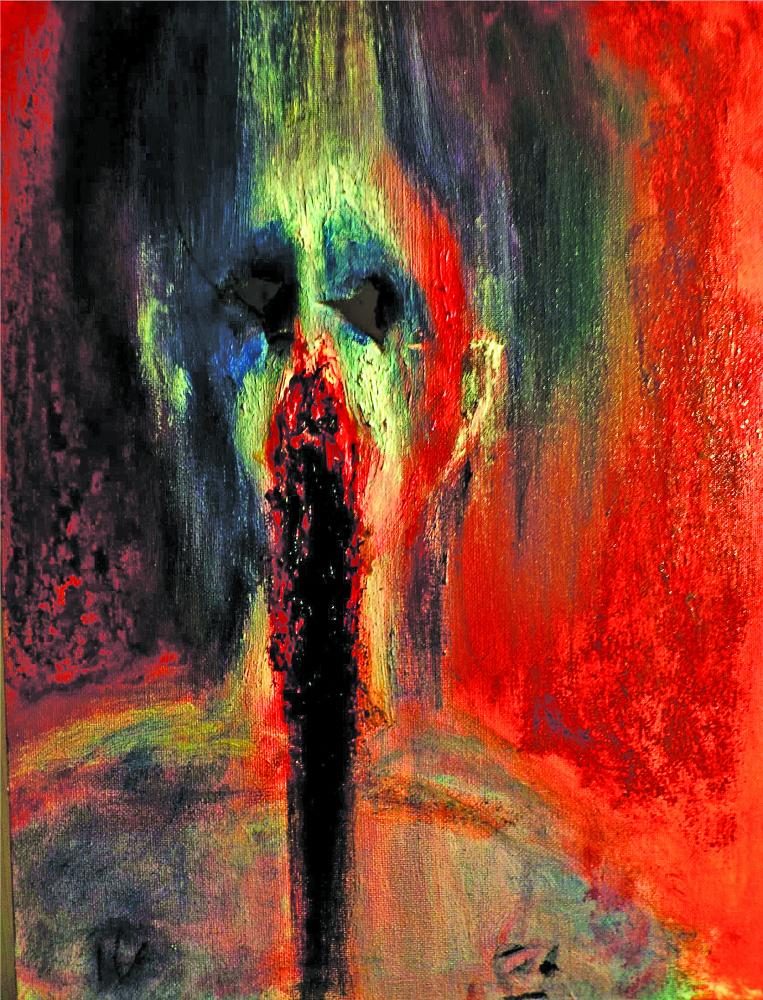

I had spent my youth struggling against behaviors increasingly beyond my control, fighting to normalize a brain that was having none of it. All the while I was unwittingly internalizing the pervasive mindset of ignorance and prejudice that surrounded me. Until there I stood, years later, studying a prescription bottle label, with shame burning hot within me. In that moment I believed myself to be as lazy and crazy and destined for failure as I had been taught the people who took those kinds of pills were. Awash with a spinning wheel of guilty thoughts, some my own and some in the voice of others, I took the first pill.

What I was battling that day was self-stigma, an issue facing many diagnosed with a mental illness, but one less likely to receive the same attention and education efforts as social stigma (that is, the societal stigma against the mentally ill). In fact, self-stigma is seldom discussed at all. However, for people struggling against this internal name-caller, finding a solution is essential.

According to psychologist Patrick Corrigan, who studies and writes about mental illness extensively, people burdened with internalized stigmatization are troubled by more than just low self-esteem. These individuals often adopt a “why try” view of life, which can impact their overall success if left unchecked. Furthermore, individuals who would benefit from professional treatment may be unmotivated to seek it because, after all, “why try?”

A Corrigan study published in the Canadian Journal of Psychiatry outlines the basic thought model when moving from social stigma to self-stigma. There are four stages to this process—awareness, agreement, application and, finally, harm. For example: a person becomes aware that the public believes people with mental illnesses are incompetent; at some point he begins to inwardly agree the public is right; he then begins to apply that belief to his idea of self (“I am mentally ill so I must be incompetent.”); the idea begins to do harm (“I am incompetent, therefore I am not capable of graduating college.”).

This last stage, often called the “why try” effect can keep a person from seeking important therapeutic help. Convinced they will never feel well again, an individual simply will not try. In my case, self-stigma nearly kept me from seeking the help I needed for a different reason. I was convinced only crazy people took medicine and I was certainly not crazy. Though the line-up of skeletons in my closet may have been long and often rattling, thanks to the impetuous and grandiose decision making a girl caught up in the throes of bipolar mania can be known for; and though I might have spent long and dark days hiding from work, from phones, from the doorbell, from the sun itself. I was not crazy.

Eventually, though, I did go for help—when I had a baby I couldn’t bond with, a house that was falling to pieces and a life I couldn’t manage another minute on my own. When I found myself standing on the side of the road wondering what it might be like to step in front of an oncoming tractor trailer truck, I went for help.

It isn’t just the stigmatization in our society that can pin a person in crisis to the side of the road desperately trying to decide if 18 wheels or a psychiatrist is worse. It is often the lies we accept for ourselves, after believing those our culture tells us, that keep us from taking off the blinders long enough to see that help is standing by. In my case, I believed the very dangerous untruths that mentally ill people are somehow less than—less strong, less brave, less intelligent, less deserving—and that no shame could be greater than that of giving in to outside help. My internal acceptance of those lies nearly got me killed.

There is, of course, hope. Without it, this would be a grim tale indeed.

Many researchers and psychologists advocate for a coming out process for those who are given a psychiatric label, stating there are positive effects to be had on the mental and physical health and well-being of those who do so. Today, psychologists advocate that individuals accept their mental health diagnosis as a part of their total identity, and studies show that those who are able to do so are more hopeful and have better self-esteem and enhanced social abilities.

This has certainly proven to be the case with me. One day I decided I was tired of hiding who I was. I realized that hiding my illness was not going to change it. I grew tired of having a dark secret hanging like a weight around my neck. And so I came out of the proverbial closet.

I suppose it might have made sense to step gingerly out of the concrete structure I had been crafting so carefully for the past decade or more. And, perhaps, in a world of my own choosing that’s what I might have done. However, when my big moment came, I was a brand new mom to a baby who was cute enough but didn’t believe in sleep, working an understaffed bar shift while adjusting to a new medication. There was no tiptoeing. There was a meltdown.

Afterward, my boss, not necessarily known for her moments of tender understanding, found me on the staff deck, where I’d escaped to. I glanced at her miserably and then away. “I’m bipolar.” She nodded and sat next to me on an empty milk crate. A moment passed before she responded in a voice that was impossible to read.

“The other day I laid on my living room floor and stared at my ceiling for two hours because I was too depressed to move,” she said. I looked at her, incredulous. She offered an expressionless shrug. “We’ve all got something.”

That moment changed everything. I was done hiding. I told everyone. I neither flaunted nor hid my diagnosis. I simply owned it for what it was, my reality. Soon I realized most people didn’t care. If anything, they were grateful to talk so openly about a topic we’ve learned to keep quiet. It has been my experience that people want to talk about mental illness.

And, so, as time has gone on, the self-stigma that held me prisoner for so long, bound tighter than my disease ever did, no longer has a hold on me. I am not ashamed of who I am, of the medication I take to help balance my mood disorder, or of the breakthrough episodes I sometimes have to explain with a wry smile of apology. Being open and conversational about my illness has allowed me to focus more on good health than on secretive living, has allowed me to work on surrounding myself with a community of friends and intimates that are caring and compassionate, and has liberated me from the shame and the ownership of a disease that is not my fault. s

Now, nearly five years later, I can look back at the memory of myself standing at the kitchen sink as though I am looking at a different woman. She and I still look more or less the same; we live in the same house, and while that babbling baby’s stream of sound has changed into talk of Star Wars battles and insects that can live without heads, it is still somehow always right behind me. In matters of vital importance, however, the woman who stood at the sink on that day and the woman I am today are worlds apart. While she stood defeated, I have accepted bipolar II as a part of who I am. I have moved past my own self-stigma and closed my ears to the social stigma still so prevalent in the culture around me.

I will no longer allow the world the privilege of defining who I am and what I am capable of.