Thurston explores living with color in “How To Be Black”

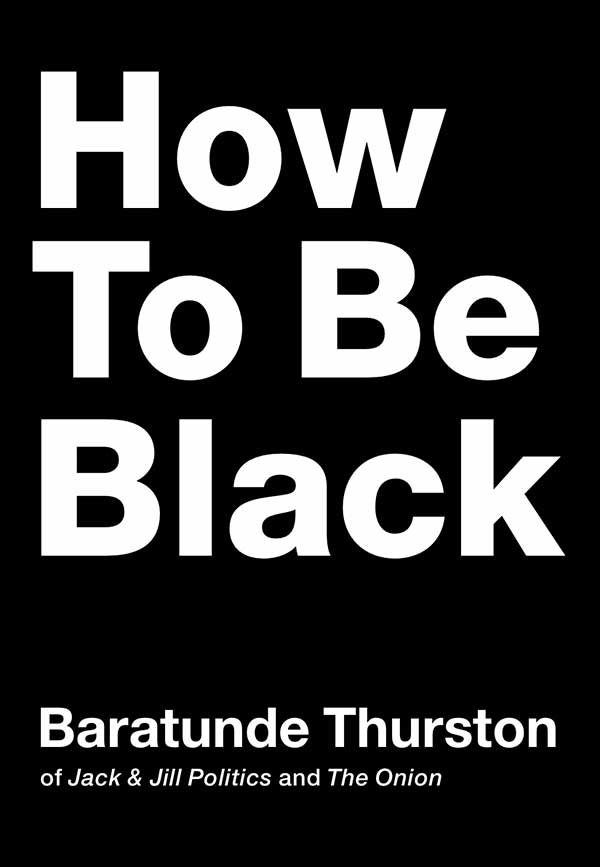

In this New York Times bestseller “How to Be Black,” Baratunde Thurston of Jack & Jill Politics and The Onion employs quick satire and humor to explore the “ideas of blackness.”

Using anecdotes from the lives of what he calls The Black Panel, an assembly of seven comedians, writers, artists, musicians, and entrepreneurs “who do blackness well,” as well as stories from his own life, Thurston successfully shares with us circumstances of injustice, pride, and self-awareness experienced by black Americans living in the sham of “post-racial America.”

He tells clearly and humorously about the seriousness of growing up in a then-drug-ridden Washington, DC, without his father, who was killed in a drug deal, but with his mother, who kept him too busy to fall into trouble and shaped him into a “miniature black activist.”

He describes attending Harvard, where he worked on the Dorm Crew, cleaning classmates’ bathrooms; on the Liquor Crew, serving alcohol at reunions and occasionally being berated by old white alumni; as a Computer User Assistant, where he found a joy for technology and provided technical support to the computer labs; and at the university’s paper, the Harvard Crimson.

While working at the paper, Thurston was able to experience first-hand the effects that diversity, or lack thereof, can have on media. Against the advice of his fellow Black Students Association members, who believed the paper was racist, he joined and soon learned that, from the inside, he could effectively sway the position the paper took on certain issues.

The chapters in this book switch back and forth from personal memoirs to uproariously ridiculous instructional narrations. In the early chapter titled “Mama Thurston,” we are told of the woman who raised Thurston and taught him to be critical of the world and active in his community, culture, and life. “She made me learn all the countries in Africa and quizzed me on them using a map on the wall of her bedroom,” he writes. “I accompanied her to community organizing meetings and stop-the-violence- vigils and black cultural festivals on a regular basis.”

Gaining this insight into who Thruston’s mother was, it is easy to understand how he became a “bass-playing, tofu-eating, weekend-camping, karate-chopping, apartheid-hating, top-grade-getting, generally trouble-avoiding agent of blackness.”

In other chapters such as “How to Be The Angry Negro,” Thurston shows the reader how to “maximize the discomfort of white people” by randomly throwing racially charged questions or statements into the air. His examples include such things as asking “How many black friends do you have?” to an unsuspecting “White Jim” or greeting an elevator full of white people by saying, “It wasn’t that long ago that people like me weren’t allowed in this elevator. The good old days, huh?”

These narrations criticize the foolish portrayal of black culture by the mainstream media and society as a whole, and encourage readers, whether black, white or other, to inspect their own behavior during these experiences, while the memoir aspect allows for a more personal connection that keeps the book’s roots in serious reality.

Thurston’s humorous approach to sensitive and enduring questions, such as “When did you realize you were black?” and “How black are you?” puts the issues discussed on an approachable platform, while also managing to root the book in a serious topic. Jumping back and forth from personal childhood stories to satirical “how tos,” and then to narratives from The Black Panel, forces the reader to think about diversity of experience and personality and the many different facets of blackness.

I would recommend this book to all those seeking a better understanding of what it means to be black in America. It is a memoir, a history, and a politically charged comedy that speaks to all people, and fearlessly confronts the embarrassment and outrage that too often accompany discussions of race. Using only his words, Baratunde Thurston brilliantly shows how to live without shame or embarrassment, but with life and color.