Du Vernay’s “Selma” gets it right

March 7, 1965. Less than a year since the Federal Government passed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 making segregation officially illegal, African-Americans still find registering to vote nearly impossible due to the arbitrary and byzantine requirements placed upon them by white-elected state and county governments. Resolved to challenge this, hundreds of civil rights activists begin the long 54 mile march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. As the demonstrators march over the Edmund Pettus Bridge just outside of Selma, they are halted by a line of Alabama state troopers. In what came to be known as “Bloody Sunday,” troopers equipped with gas-masks advance on the marchers, beating them with nightsticks while the hazy tear-gas laden air stings their lungs.

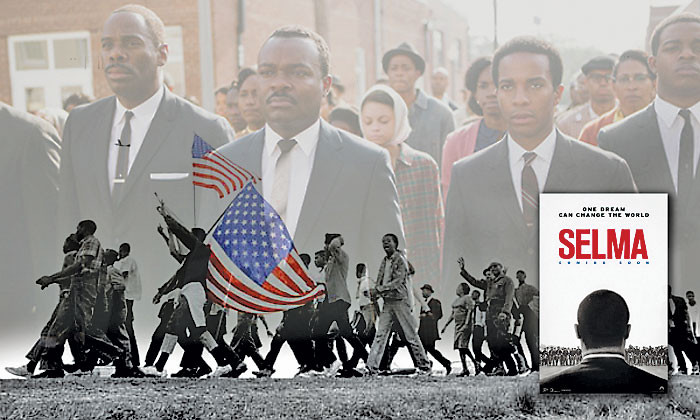

This dramatic scene is the real historical backdrop to Ava DuVernay’s film “Selma.” Though this kind of action-packed spectacle almost leaps onto the screen by itself, the film doesn’t linger here excessively, opting instead for a focus on the behind-the-scenes work of Martin Luther King Jr. and the other activists of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. The resulting balance of factual history and cinematic flair involves us in the events without becoming overwhelming.

A major highlight of the film is the peek into the personal troubles between Martin and Coretta Scott King (Carmen Ejogo), which we see so rarely in the historical coverage of the couple. King is nearly regarded as a saint for his public role as the leading figure of the civil rights movement, but by letting us witness the intimate conversations with his wife over his infidelity and the constant threat of death, we are allowed a glimpse of the real, flawed, human being sheltered beneath the apotheosis. Every scene with Martin and Coretta is revealing, yet executed with taste and finesse.

The acting in “Selma” is top-notch and by itself is reason enough to go see it. David Owelowo’s performance is a major plus; it’s all too easy to forget he’s actually a British actor given the authenticity with which he channels King’s methodical Georgia accent. The whole cast gave excellent performances, not a single actor was sub-par or even mediocre.

The soundtrack is good, but not exceptional. The majority of the tracks are from the period, with a few originals included. Gertrude Morgan’s rendition of “I Got the New World in My View” is particularly moving, and hearing Martha Bass’ “Walk With Me”, play as the marchers are attacked on Bloody Sunday transforms horror into a religious experience. I wouldn’t purchase the soundtrack, but it fits very comfortably within the context of the film.

It was surprising and welcome to see “Selma” avoid the usual tropes and show the morally ambiguous relationship between the civil rights movement and the federal government, particularly in the behavior of the FBI and its director J. Edgar Hoover (Dylan Baker). More often than not scenes involving King and his associates feature the mechanical tap-tap-tapping of a typewriter documenting their actions, reminding us of the paranoid obsession with which the FBI spied on the SCLC. “Selma” shows us that it wasn’t just good ol’ boys and the Southern political class who had it out for King. In Hoover’s own words, spoken in real life and in the film, “King is a political and moral degenerate.”

One of the film’s weaker elements is the lack of oratory power in the portrayal of King’s speeches. Owelowo seemed markedly less comfortable portraying King the speech-maker than King the conversationalist. More importantly, however, the Martin Luther King Jr. estate did not allow “Selma” to use his actual speeches, because they had already been licensed for a Warner Brothers biopic. What we hear in the film are only paraphrased copies that capture the content well enough, but unfortunately lacking the poetry of King’s original words. The film itself can’t be blamed for this, but it subtracts from the final product nonetheless.

The film has drawn ire from several critics as well as Joseph Califano, a former aide to President Lyndon B. Johnson, over its less-than-amicable portrayal of the relationship between King and Johnson. This is warranted to some extent— Johnson never approved of or asked for Hoover’s attempts to destroy King’s marriage with Coretta— but such criticisms ultimately miss the mark. Films about historical events must take some artistic license in order to create a compelling narrative. The real question is, what does the director choose to emphasize, and why? In “Selma”that emphasis is on the leading role that black activists played in the battle for their civil rights, a welcome change from films like “Mississippi Burning” with its portrayal of whites employed by the FBI as the heroic figures.

Boasting terrific treatment of the subject matter and heavyweight acting by the cast, “Selma” is an instant classic. Anyone holding even a passing interest in the Civil Rights Movement or Martin Luther King should go watch it immediately.