Eco-Band keeps the dead alive

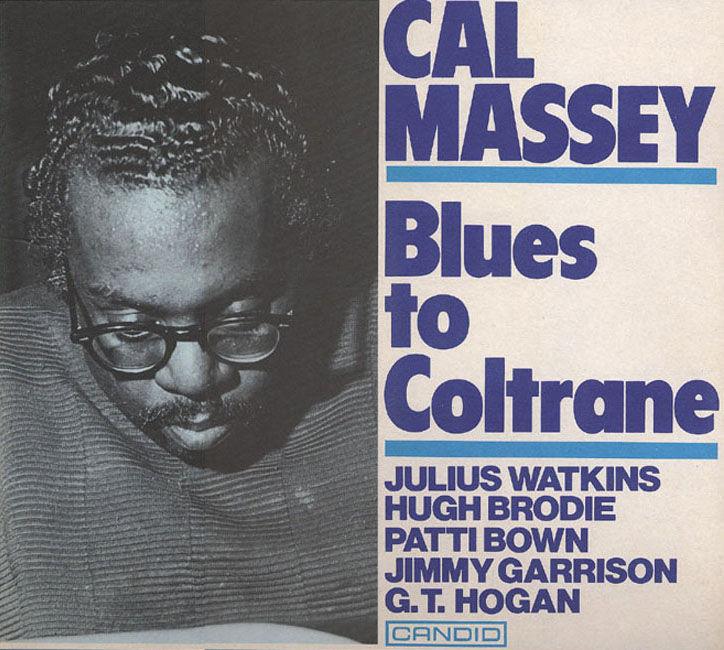

The “Eco-Band” celebrated jazz composer Cal Massey

An African-American woman dragged herself across the stage. Years weighed her down.

She started by thanking Goddard College. Audience members looked at each other.

Someone yelled, “This is Johnson State College!” The speaker didn’t understand. The someone repeated, “This is Johnson State College!”

The old woman got it. “Johnson State, do you forgive me?”

The audience applauded. Then the speaker launched into a speech so thunderous it would’ve shaken Mount Olympus.

She said she’d been through civil rights riots. She’d been there in the heyday of the civil rights movement.

“But the thing that is most important to me,” she said, “is I came through your snowstorm.”

The speaker said she’d kept her eyes on the double yellow lines in the road. “The tracks,” she said. “Through the storm, I kept my eyes on the tracks”—just as she kept her eyes on the tracks through the storm of the civil rights movement.

“YOU—are the road builders,” she said. Her voice needed a microphone like a sauna needs a furnace.

She bellowed, “Stand. I invite you to stand. I am, because you are.”

This was Wed., Feb. 19, in Dibden. The doors opened at eight, but it was nine before the music started. It turned out to be a night of politics as much, and maybe more than, music.

The show was simply advertised as “Eco-Music Big Band.” It was a Creative Audience event, but the seats weren’t half full. Three people left during the show. The rest stayed for the entire two-and-a-half hours of oral and aural sensation.

The speaker didn’t identify herself, and I can’t find her name on any of the websites advertising the event, or on the Scientific Soul Band’s official website. The Scientific Soul Band is the actual name of the “Eco-Music Big Band.”

Anyway, after her opening invocation, the speaker gave the stage to Claire Dolan. Dolan is a veteran of the Bread and Puppet Theater, a political puppet theater active in Vermont since the Sixties. Dolan is also the director of the Museum of Everyday Life, in Glover.

Dolan did an electric, focused charge of a presentation on Cal Massey, the man of the evening, an African-American jazz composer born in 1927 and dead in 1972. Dolan’s presentation was on sticks.

Two sticks, each held by a JSC student, supporting a canvas with colored sketches (the kind of sketches to be framed and hung in an art show).

Dolan yelled, “Who was Carl Massey?”

Two saxophonists from the band played a wild 10-second ditty every time Dolan finished speaking. It went like this: Dolan describes a piece of Cal Massey chronology; saxophone; Dolan rips off one of those sketches, to reveal another underneath, or flips over the canvas; and repeat.

Anyone paying attention knew who Carl Massey was by the end of the presentation—not just how he happened, but a sense of the man himself. Dolan pulled off surprising intimacy in the 10 minutes of the presentation.

Which ended with this line, scrawled at the bottom of the final canvas: “Culture starts with the people as creators of themselves, and transformers of their environment.”

The unidentified speaker returned. She said she’d hung with Cal Massey in ’72, before his death.

She said, “Cal Massey will live, and never die. We know he can’t die—because he’s here with us, in this room, tonight.”

Salim Washington took the stage. The speaker said Washington hails from Africa. He’s a tenor saxophonist and a scholar of jazz.

Washington said music overcomes the language barrier—that music becomes a meta-language. He said that any music teacher will teach you that musical compositions are based on musical consonants vs. dissonants. He said that blues was built on creative use of those dissonants. Metaphor. METAPHOR!

Washington also said jazz represents “increasing degrees of freedom.” He said that, “trapped in [Cal Massey’s] beautiful melodies is turmoil, a struggle, a yearning.”

Then, finally, at 8:54, the Scientific Soul Sessions Band took the stage. It struck me that the band was more than half white.

They played Cal Massey’s “Black Liberation Movement Suite.”

The first movement, “Prayer,” segues into movement two: “Hey Goddamit, Things Have Got to Change.”

The suite began with a catlike sway between bursts of righteous fury. Then came pained strings. When Washington said Massey’s music mixed turmoil and beauty, he wasn’t kidding. It sounded like bipolar music, striving for harmony between extremes.

The cymbals picked up. The sax frenetically wailed. The collective cries of the band sounded like brass under duress. The violin wept. The conductor, a young woman in purple pants, shook her backside as the groove rose. The band members called, “Hey, goddamit!”

Next movement: “Three Men at Peace in Algiers.” It sounded like peace. It sounded like death. The music rose like watching a woman unbutton her robe, then fell like watching her walk out of the room.

The music picked up. Triumphant wails. The sax player flipped out.

Movement four arrived: “Black Saint (For Malcolm X).” A stabbing crescendo. It sounded like fear. The bass heated up.

The song turned into an ecstatic storm, thumping, screeching, trumpeting, regal, dignified. There was a fierce clarinet solo.

And we arrived at movement five: “Peaceful Warrior (For Martin Luther King, Jr.).” Which didn’t open peaceful—it sounded like a nightmare. Eerie, chilling piano lulls. Squealing sax. Then it sounded content, like we imagine a shaded afternoon on a Hawaiian beach. Massey’s music is definitely a study in contrast.

Movement six: “The Damned Don’t Cry.” It sounded like Lauren Bacall walking into a room. It had that kind of va-va-voom squawk. Then it picked it up: it sounded like jolly New York hustle ‘n’ bustle. Then back to the squawking.

Then the trumpet burst and the band exploded into such fierce rhythm it could’ve put a child through puberty.

Movement seven: “Reminiscing About Dear John (For John Coltrane).” Shrill trumpet, gentle sax, magic piano, soothing drums. Sounded like Coltrane’s “I’m Old Fashioned,” off “Blue Train.” Felt like coming home to serenity, or safety. It was too short.

Movement eight, “Babylon,” segued into movement nine, “Back to Africa.” It was an instrumental attack. It mellowed down, then rose again to a cacophonic rally. Then: an explosion of rhythmic bliss. A thumping, dangling rhythm. And it was over.

The night wasn’t. The author of “Truth and Dare: A Comic Book Curriculum for the End and the Beginning of the World” took the stage. Among his statements: “You’re all happy for a free show, I’d hope the LEAST you could is pick up this book.” He also advertised something “so special”: there was a deal if you got 2 CDs. This was a night of cultural appreciation, championing freedom and celebrating the spirit, and here’s this guy trying to guilt us into emptying our wallets.

He left the stage, and the night continued. Turns out the conductor was jazz composer Fred Ho’s last student. Fred Ho, composer of “The Scientific Soul Revolutionary Guardens of Harlem Suite,” which closed out the night. The conductor composed the first two movements; Ho composed the third movement himself, his final composition.

As it happens, jazz is a better channel to the dead than a Ouiji board. Far better.