“Ender’s Game” still enjoyable almost 40 years later

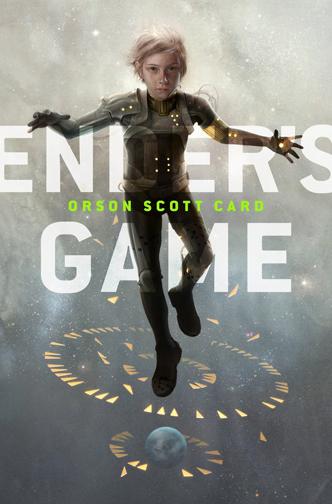

The new edition of “Ender’s Game”

Orson Scott Card’s “Ender’s Game” first came out in 1977. I read it then, and enjoyed it so much that I went on to read the rest of Card’s work as it came out. I didn’t expect to read this particular book again, but since it showed up on our “New Books” display last month here in the Willey Library, I decided to look at it again and review it.

In the book, we follow a very young, gifted boy—Ender—as he journeys through a military-type school and plays very competitive battle games. The school and the games are played in space.

The story itself is fast-paced and engaging; it is written in stark dialogue that moves quickly. Reading “Ender’s Game” from the perspective of an adult and a parent, it’s not the story but Ender’s personality that fascinates me this time around.

Gifted children have distinct characteristics. One common characteristic is that they can think way beyond their years, even though they still may have the body of a six-year old child, like Ender.

Isolation is a big theme in this book, something Ender struggles with from the first day of his journey. It’s easy for a gifted child to feel isolated; many people who interact with gifted kids just don’t get them—including extended family and teachers.

Gifted kids compensate, as does Ender, and it is interesting to see how he thinks and makes decisions. He has strong compassion despite his circumstances, and ultimately this compassion is the bridge to Card’s sequel book, “Speaker for the Dead.”

We never know by the end of this book whether or not Ender considers his life fulfilling. It’s hard to imagine how he’d consider it so, but as a reader, you want him to reach some level of happiness. He may not feel fulfilled, but he definitely is engaged, and with gifted kids (and adults, for that matter), engagement often has more merit than fulfillment.

When you read “Ender’s Game,” keep in mind that one in every ten U.S. children is like Ender. Gifted children really exist, and like Ender, they have special needs. When I first read “Ender’s Game,” I was still in high school. Now I’m raising two gifted kids of my own, and Ender’s character and his actions make a lot more sense.

In the introduction to this recent printing of “Ender’s Game,” the author shares his thoughts about gifted children, so you know as a reader (if you are the kind to read introductions) that Card is trying to make a point. Ultimately, though, what you care to know or not know about gifted children doesn’t matter. “Ender’s Game” as a science fiction story is strong enough to stand on its own.