It’s a tale as old as the Bible. But the Bible involves people who have sex – and it never had this much gore.

This tale is more akin to a story spun by the wise old Greeks: the tale of Prometheus, who stole fire from the Gods and brought it to humankind. The Gods then chained Prometheus to a rock, and buzzards ate his heart out.

If only we’d asked for less than 10 grand.

Cast of characters: Benjamin Algar, the Prometheus in our modern variation; and Martin De Geus and myself, two Calibans to Ben’s Prospero. Ben’s concern was such stuff as dreams are made on, like Prospero. But sometimes, the sunlight of our dreams so blinds us that we reach past them, into the clouds – and come out only with hands full of fluff.

And definitely not 10 grand.

I discovered Kickstarter in the bitter chill of March: a sensational website funding independent art through donations. One sets a fundraising goal – like 10 grand – then creates a page explaining their project, their intentions, and how they are going to make it happen. Users then donate money to the project, an amount of their choosing, for a period between 30 and 50 days.

If the project raises as much as or more than their goal, the project founder receives the pledges, and can go to work. If the project doesn’t raise as much or more than its goal, no one gives or gets shit.

I decided to create a web series on Kickstarter. I wrote five potential series over a week, picked the most financially plausible, and began preparing a Kickstarter with Martin. I wanted to shoot for $2,000; Martin convinced me to up it to $4,000. We were just about to launch…

When “Seeking a Friend for the End of the World” came out, with Steve Carrell and Keira Knightley. It was my project to a tee, only mine included dozens of goats, a witch, superpowered characters (a dumb romantic allegory), and an alien.

I explained this to Martin and Ben as we guzzled booze around a midnight fire like Cadillacs at a gas pump.

“I have this idea I just outlined with my dad,” Ben told us. “If you’d like to hear it. We finished it at the beach on Sunday.”

It was called “Zombie Café.” Ben and his father had named its protagonist Hermes Trout. (Shades of Kurt Vonnegut, from whom we borrowed our motto after this whole bloody affair: “So it goes.”)

Hermes was a banker pre-zombie apocalypse. Post-zombie apocalypse, he gets his only source of social amusement pretending to be a zombie at a local café. He puts on zombie makeup to blend in. He encounters a human woman on her way to the Big City, and they develop a thing, just as one of the zombies, who herself had a thing for Hermes back when her heart beat, rediscovers that loving feeling.

Martin and I loved it.

“‘Doomsdate’’s toast,” I said. “Go for ‘Zombie Café.’”

Ben was the antithesis of his zombies. He did everything possible to form a sturdy business cradle for “Zombie Café.” His father looked up the title “Zombie Café” and found a young-adult author in California owned the rights. Ben retitled the series “Zombie Diner.”

“It just doesn’t roll off your tongue like ‘Zombie Café,’” he said.

“‘The Evil Dead’ doesn’t roll off the tongue like ‘Blue Velvet,’” I replied. “It’s the material that makes the title work.”

“The Evil Dead” became our business model. Its producers, Sam Raimi and Rob Tapert, had been our age when they began making the film. Ben created a production company for our work, an L.L.C. named Frame Diner Productions, which surprised Martin and me like Carrie’s hand shooting out of the grave at the end of “Carrie.”

Was this the birth of our careers? Would we be bursting from the popular-art womb every time a zombie thrust its arm through an unsuspecting pregnant woman?

Am I petting 10 grand as I write this?

It didn’t help steady our production that Ben was in Old Lyme, Connecticut, home of sunsets and biddies on the beach, I was in Springfield, Vermont, home of the Simpsons, and Martin was in Calais, Vermont, home of him. Coordinating production was like Zeus doing the mambo: a lot of shaky-footed stomps and drunk-bellied sways with thunderous cursing.

Ben is a born businessperson. He handled Kickstarter’s financial verification process, which consists of having one’s taxes, credit cards and bank accounts verified, with the slick skill of a Hollywood mogul, the tan skin of a Hollywood star and the chattiness of a suburban grandmother.

Martin and I were no help. We were the production crew: we were just telephone voices until production began.

But we might as well have been on the other end of a phone sex line. Ben’s embers burst into flames. We stoked the fire every time he called, and he set our own embers glowing.

“I’m developing a 10-year plan,” he told me.

Ben was going to buy stocks, then sell them. He had a plan for Frame Diner Productions, L.L.C., to become a $1,000,000 business within 10 years. He had gone from Shia LaBeouf in “Disturbia” to Shia LaBeouf in “Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps.”

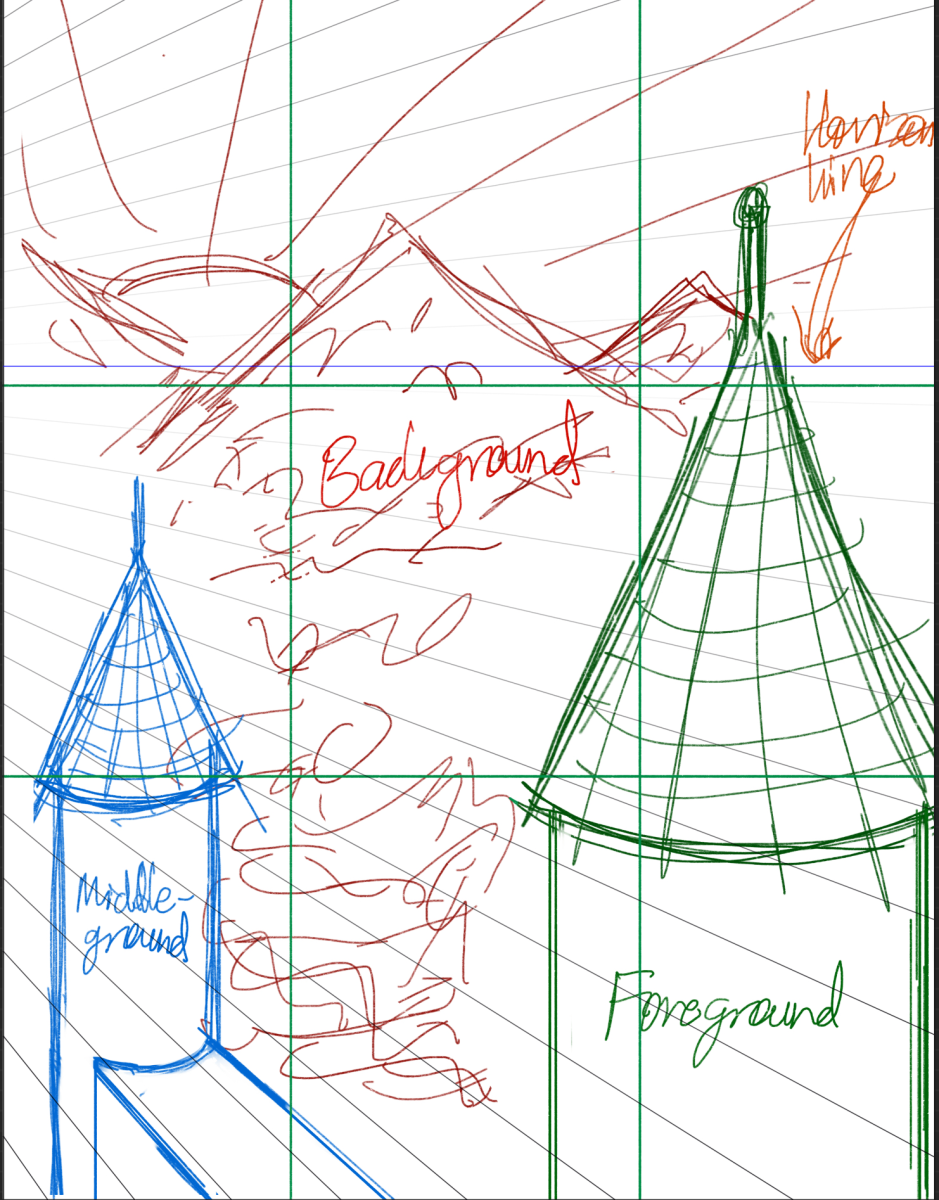

We needed to shoot a short video for our Kickstarter page, something around five minutes long that would give potential investors a sense of our project. I gave Ben an example: we could have a Robert Altman-esque minute of a guy lounging on a beach, lots of dissolves, and just as we dissolve to him taking a nap by the water A ZOMBIE BURSTS OUT OF THE WATER AND EATS HIS GUTS — and then we cut to the three of us in a conference room, where Ben rejects the idea.

We cut to another zombie scenario… and so on, culminating in a clip from “Zombie Diner,” which Ben would give an enthusiastic, “Ohhhh yeah!” It would give people a sense of the pointed humor for which we were going: it would show that we were heading for something like George Romero’s “Casablanca.”

“I like that,” Ben wrote, the 99th reply in a string of Facebook communications. “Let’s do it.”

Martin and I drove to Old Lyme for a weekend. We got sunburned and picked up poison ivy on our feet. I learned I was not just good at badminton against my brother, and Martin learned he could play volleyball with knockout dames and keep his cool. Ben’s sister threw a toy snake in my face, and a pre-teen member of Ben’s family viciously wrestled to take the snake from my grasp in the enormous crystalline pool beside Ben’s house. We had Kahlua in Ben’s hot tub at night and worked out the logistics of shooting our promo.

The high school girls monitoring the oceanside parking lot didn’t want to act in it. Ben’s brother was too busy to shoot the beach scenes. The anxious-eyed brown-skinned woman on the beach towel valiantly fought her primal desire to press charges when Ben asked for her involvement.

We shot the promo at Ben’s house. I noticed my concept for the promo had been dismembered like the human flesh to be served at the Zombie Diner (Where was the beach? Where were the different concepts between which we were cutting? Why was Martin lying on the hood of Ben’s car, filming a terrified citizen fleeing from a zombie?). I chalked it up to Ben’s auteurial vision: he was the John Carpenter of seaside Connecticut.

Ben’s brother, Nathan, consumed Martin’s corn syrup blood, gargled this gory mouthwash and then ejaculated it like Linda Blair until his body was splattered with it. Nathan is the undead Dustin Hoffman: he strips his personality until only the zombie’s lacking energy charges through him, and he sputters nonsensical outbursts like Rain Man.

We got it all on tape.

We didn’t put a lot of thought into how we would film Ben’s AMC-scaled four-part hour-long web series around our college schedule: Ben had graduated and was working as a tennis instructor, but Martin and I were still enrolled at Johnson State College and going nowhere fast. Our wallets were as tight and shriveled as male privates in an arctic plunge. Driving to Old Lyme on the weekends to film “Zombie Diner” was barely plausible.

Then Ben sang like a siren.

“If this project is a success,” he cooed, “it might not be a bad idea for you guys to take a semester off.”

Ben floored the bandwagon’s gas as soon as our feet left the ground.

Why not? We all wanted to make films. That was all we wanted from our lives. We would barely make enough to survive with our first projects, but as our popularity grew and the scale of our projects increased, we might be making enough off which to live. It seemed feasible that we would be self-employed and financially satisfied within a year.

Granted a year’s not up yet.

We made the decision that if “Zombie Diner” were fully funded, Martin and I would seriously consider taking a semester off to produce the series.

Somewhere else someone resolved that if pigs learned to fart music, they’d take a semester off, and they remain closer to doing so than us.

Ben watched other Kickstarter promo videos and decided we needed to be filmed talking about our project: that’s what all the other potential fundees were doing. I imagined the first promo video to fight that routine, but Ben the Businessman preached safety first, and if he thought it would get us 10 grand, why not?

There’s $93 in my wallet.

We reconvened in Springfield. My childhood home was on the market and empty: my recently divorced parents were living in separate homes with new families. The house became Frame Diner Productions, L.L.C.’s production offices for the last weekend before our metaphysical cataract surgery.

Getting whiskey and beer was our first objective. Our second was purchasing toilet paper, makeup tools, glue, vegetarian hot dogs, dye, corn syrup, flour and a watermelon.

The toilet paper, makeup tools, glue, corn syrup and dye were for Ben’s zombie makeup. The vegetarian hot dogs and flour were to make my fake intestines, which I would pretend to eat.

Ben wanted the watermelon carved in the shape of a zombie’s face, and then he wanted to blow it up. Ben’s scripted opening for our second promo video involved a man running in the background on fire, and then the zombie-faced watermelon exploding. Martin and I convinced him to simply have a normal zombie in the background, and to light a smoke bomb in the watermelon.

Ben was disappointed.

Ben and Martin stayed up until almost four in the morning editing the second promo video. They continued editing from 10 in the morning to 3 in the afternoon. I don’t need to describe the product: you can see it online on the Basement Medicine website.

I composed the promo’s twinkling piano score after taking off my shirt, drunkenly proclaiming, “I’ll show you genius,” and sitting down at Martin’s keyboard for five minutes.

The last thing on which we had to agree was budget. I proposed a $2,000 budget. I agreed on an $8,000 budget after Ben said he was sure we could raise it.

Ben and his father drew up their own budget, which came to $25,000. Martin agreed.

I argued for something far lower, and we met in the middle at $13,000. We eventually and barely settled on $10,000, which Ben and Martin agreed was the bare minimum with which Ben could make his series.

The Kickstarter went live on July 17. It died on July 18.

We all sat around our computers in our respective hometowns on July 17, clicking refresh. $25 came in. Then $50. $200. We’d raised $645 by the end of July 17.

We’d raised $745 by August 16, when the fundraising drive ended.

We slithered through the weeks between those dates like the boat from “Apocalypse Now,” drifting into deeper and darker territory. Hours squeezed out hope like a tight fart. Ben’s optimistic updates seemed decreasingly genuine. Our future was a dream from which we were groggily waking up.

Martin and I have considered trying our own Kickstarter projects, something less ambitious than “Zombie Diner,” like a short film. Ben plans on going to graduate school for pre-med. Maybe he’s burying and drowning his magic, like Prospero.

But “The Tempest” has an epilogue. Prospero, stripped of his magic, asks the audience to set him free with their applause.

Costs a hell of a lot less than 10 grand.